Securing digital assets like cryptocurrencies and NFTs is a tricky business, as demonstrated by numerous losses and heists. The challenge of storing digital assets applies equally to individuals and to larger actors - from companies to cryptocurrency exchanges to the largest financial services corporates.

Digital assets are secured (almost exclusively) with cryptographic signing keys. But from the early days of Bitcoin it was clear that our mechanisms, which worked perfectly well in the olden days, are inadequate. Our mobile devices are (maybe) secure enough for our emails, but not for cash. Plastic cards work for authorizing transactions if we can cancel them with a phone call, but that’s not the case with digital cash that has no “undo”. Indeed, for securing digital assets it is not uncommon to use multiple keys.

But how many keys should one use, what type, and how does one design her wallet? We took some first steps towards answering these questions, starting with a simple model and basic analysis that very quickly reveals surprising results. We start with the basic (natural, but new) definitions and outline our results.

If you are interested in the details see the paper here. You can also play with our online wallet designer (details below).

Reasoning about key faults

The first thing to do is understand what can happen to an individual secret key. Each key might be lost (unknown to anyone) or leaked (known to the owner and to an attacker). This leads to a tension. Storing keys in ways that are less likely to be lost (e.g., multiple copies) often makes them more likely to be leaked. Keys might also be stolen, so an attacker has them but the owner doesn’t - for example if stored with a third party that gets compromised.

There is a certain probability for each fault, and we assume the faults are independent for different keys: The probability for key 2 to suffer loss is independent of whether key 1 experienced a fault.

To make any design choices we’ll need estimates of those probabilities. Unfortunately, there is no public data with statistics, and so you have to answer this yourself. For each of your keys - committed to memory, written on a note, stored on your phone, or online, what are the chances of it getting lost, leaked, or stolen? Given those probabilities, we can design our wallet.

Wallet Design

A wallet is implemented in a smart contract along with an off-chain architecture (e.g., using threshold signatures). To put simply, the user authenticates with one of several possible sets of keys (maybe 1&2, maybe 1&3&4). To put less simply, the wallet is a monotone boolean function of key availability. The wallet fails if either an attacker gets the money (enough keys were leaked or stolen) or if the owner can’t access it (enough keys were lost or stolen).

So we can try all the possible wallets and use the one that results in the lowest failure probability. Or can we? The number of monotone boolean functions is the Dedekind number, which grows so quickly we only know its value up to 8 variables. Our case is smaller by 2 (since we don’t care about the functions “True” and “False”), but that’s still too large to scan.

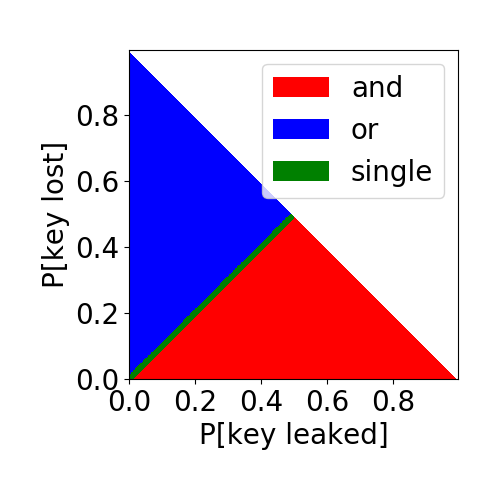

Nonetheless we discover some interesting results in the feasible range. For example, with just two keys, if there is a positive theft probability (1% in the figure below), then if the loss and leak probabilities are similar the optimal wallet is using just one key and not both.

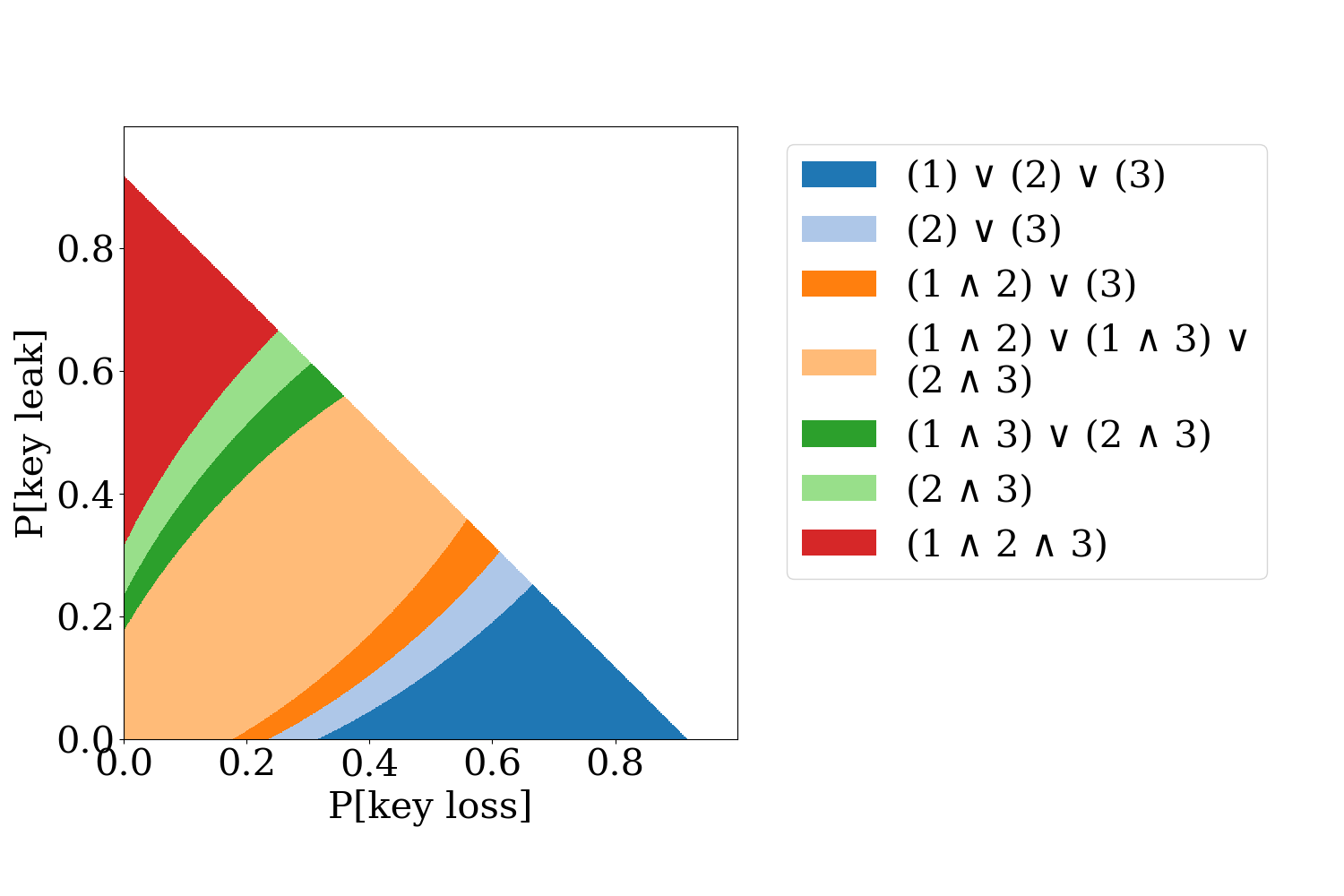

With three keys things become even more interesting, (8% theft probability):

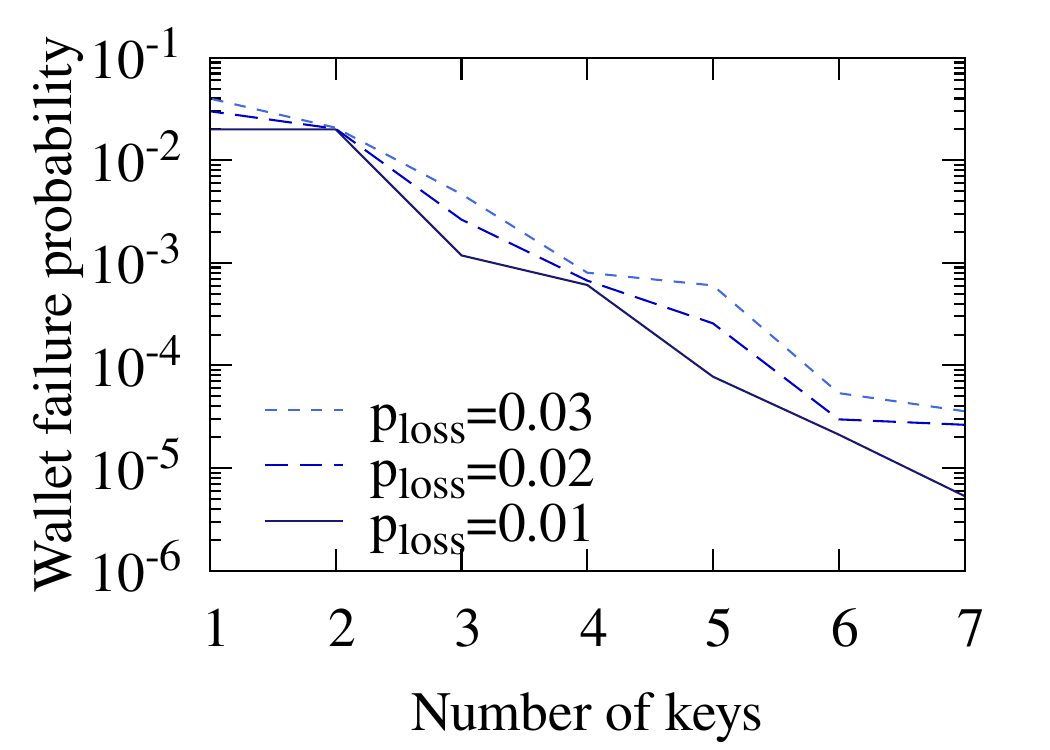

A critical question when designing a wallet is how many keys to choose. The figure below shows that the exponential decrease of failure probability makes quantity more important than quality. Six (6) keys with a loss probability of 3% result in an order-of-magnitude safer wallet than three (3) keys with a loss probability of 1% each (all keys have a theft probability of 1%):

Calculator

You can experiment with the model by evaluating different wallets using our wallet designer. Enter the probabilities for the keys, design a wallet, and see its failure probability. You can also click to find the optimal wallet for up to 4 keys.

A couple of points about the calculator:

- This is for gaining intuition and experimenting with the model. Not for real money.

- The calculator runs locally on your browser.

- The code is here, courtesy of ZenGo, developed by Shalev Keren (@shalev0s).

We appreciate any contributions and comments.