TL;DR We have discovered a denial-of-service attack on Bitcoin-like blockchains that is much cheaper than previously described attacks. Such blockchains rely on incentives to provide security. We show how an attacker can disrupt those incentives to cause rational miners to stop mining. Technical report here. Original blog post here.

Denial of service (DoS) attacks have been plaguing the Internet since its early days. DoS attackers target various services for fun and profit. Most commonly, they flood a server with requests that leave it too busy to serve legitimate users. Countermeasures often prevent naive implementations of this attack by identifying sources of flooding. Attackers must therefore orchestrate flooding from many machines in so-called Distributed DoS (DDoS) attacks.

Fun fact: the distributed sources are often unsuspecting users’ compromised machines that form a network of bots, or a Botnet.

Cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are a particularly lucrative target for a DoS attack. In principle, futures markets and margin trading allow an attacker to short-sell a cryptocurrency, reaping a profit by crashing the currency’s price. Competing cryptocurrencies and governments worried about the impact of cryptocurrencies on financial sovereignty are other potential attackers. To the best of our knowledge, however, in practice no successful DoS attacks have been made against prominent cryptocurrencies.

The reason is the decentralized nature of blockchain protocols. In a blockchain, there is no central server to attack. The machines operating a blockchain, called miners, all fully replicate the blockchain data. While attacks against individual machines have been known, a complete shutdown or even compromise of several machines have little effect on the availability of the system as a whole.

Even funner fact: Bitcoin’s peer-to-peer network is built for robustness against attacks, taking lessons from botnets built to be resilient to counterattacks from anti-malware companies.

In fact, known DoS attacks against blockchains like Bitcoin are extremely expensive. The Bitcoin protocol, suggested by the pseudonymous Satoshi Nakamoto, relies on Proof of Work (PoW) for security. Miners may only create blocks by proving they have expended resources outside the system, namely computing power. Blockchain security is only maintained when the majority of the computing power in the system behaves appropriately. A DoS attack could, therefore, be executed by an attacker with more computational power than all other participants combined, a.k.a. a 51% attack. For major cryptocurrencies, 51% attacks are prohibitively costly for most entities.

Such attacks were attempted during the “hash wars” between Bitcoin ABC and Bitcoin SV at the end of 2018, with limited success.

Enter BDoS

We find that the inherent properties of Nakamoto’s protocol expose it to significantly cheaper DoS attacks. We leverage the fact that Blockchain protocols rely on incentives for security. Blockchain participants, called miners, are rewarded for their participation with cryptocurrency. When those incentives no longer align to promote good behavior, the system is at risk. Our attack, called Blockchain DoS (BDoS), exploits miners’ rationality by awarding them higher profit for playing against the system than following its rules.

For full effectiveness, the attacker needs the miners to be aware of the attack and of the fact that they can increase their profits by misbehaving. This strategic behavior is obviously not pre-programmed in mining software. Therefore, we believe the attack does not pose an imminent risk, as miners would have to reprogram their mining equipment to maximize their profits when faced with an attack.

The existence of such an attack is perhaps not a surprise, it is indeed a manifestation of the theory presented by Bryan Ford and Rainer Böhme, who argue that analysis of a system in terms of rational agents is of limited utility, due to exogenous incentives that are indistinguishable from Byzantine behavior.

Below we outline below the mechanics of our BDoS attack. But first, for foreigners to Nakamoto’s land, let’s start with some background.

Background

The vast majority of cryptocurrencies (in terms of market capitalization) use the blockchain protocol proposed by Nakamoto for Bitcoin. In the Nakamoto blockchain, all transactions in the system are placed in blocks, which form an ever-growing chain. Miners extend this chain by forming new blocks with fresh transactions, which they publish to all other system participants. The rate of block production is regulated by requiring miners to include Proofs of Work — -solutions to cryptographic puzzles — -in their blocks. (A block without a PoW is by definition invalid.) To compensate miners for their effort, block generation is rewarded with some set reward (e.g., 12.5 Bitcoin per block as of today). If miners are not too large, they are thus incentivized to extend the chain and collect rewards.

Since miners are spread across the globe, occasionally two or more miners generate blocks concurrently. These blocks have the same parent. The result is a fork, where the chain has multiple branches. To identify a single chain to be extended, Nakamoto’s rule is that the longest chain is the main chain, all miners should extend it; blocks that diverge from that chain, as well as their rewards, are ignored.

To avoid loss of rewards, miners have been known to start mining before they receive and validate the latest block. Instead, they start mining on the latest block once they receive its metadata in its header. They thus avoid wasting mining resources on old blocks and increase their chance of mining the next block. This is generally not good practice and raises security concerns outside the scope of this post. This approach, of mining based on a header, is referred to as SPV mining, after the legitimate Simplified Payment Verification protocol used by lightweight clients for partial blockchain validation.

The Attack

The BDoS attack we introduce brings a blockchain to a halt by manipulating the rewards for rational miners. The attacker brings the system in a state where the best course of action for rational miners is to stop mining. She proves to other miners that the system is in this state.

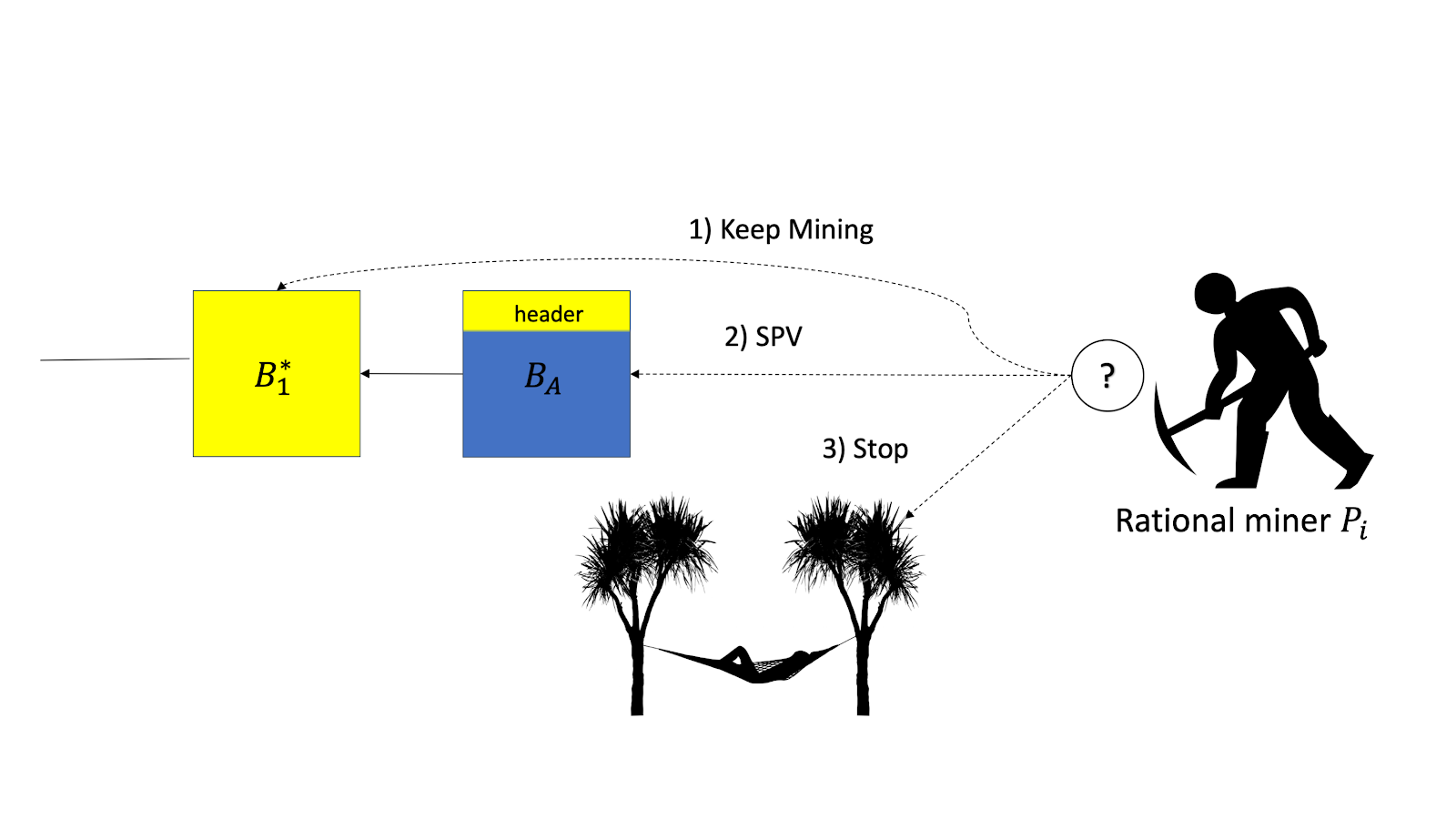

To induce this state and the accompanying proof, the attacker generates a block and publishes its header, and only its header. Given a header, a rational miner has three possible actions: (1) She can extend the main chain, ignoring the header, (2) She can extend the block header (SPV mine), or (3) She can stop mining, neither expending power nor winning rewards.

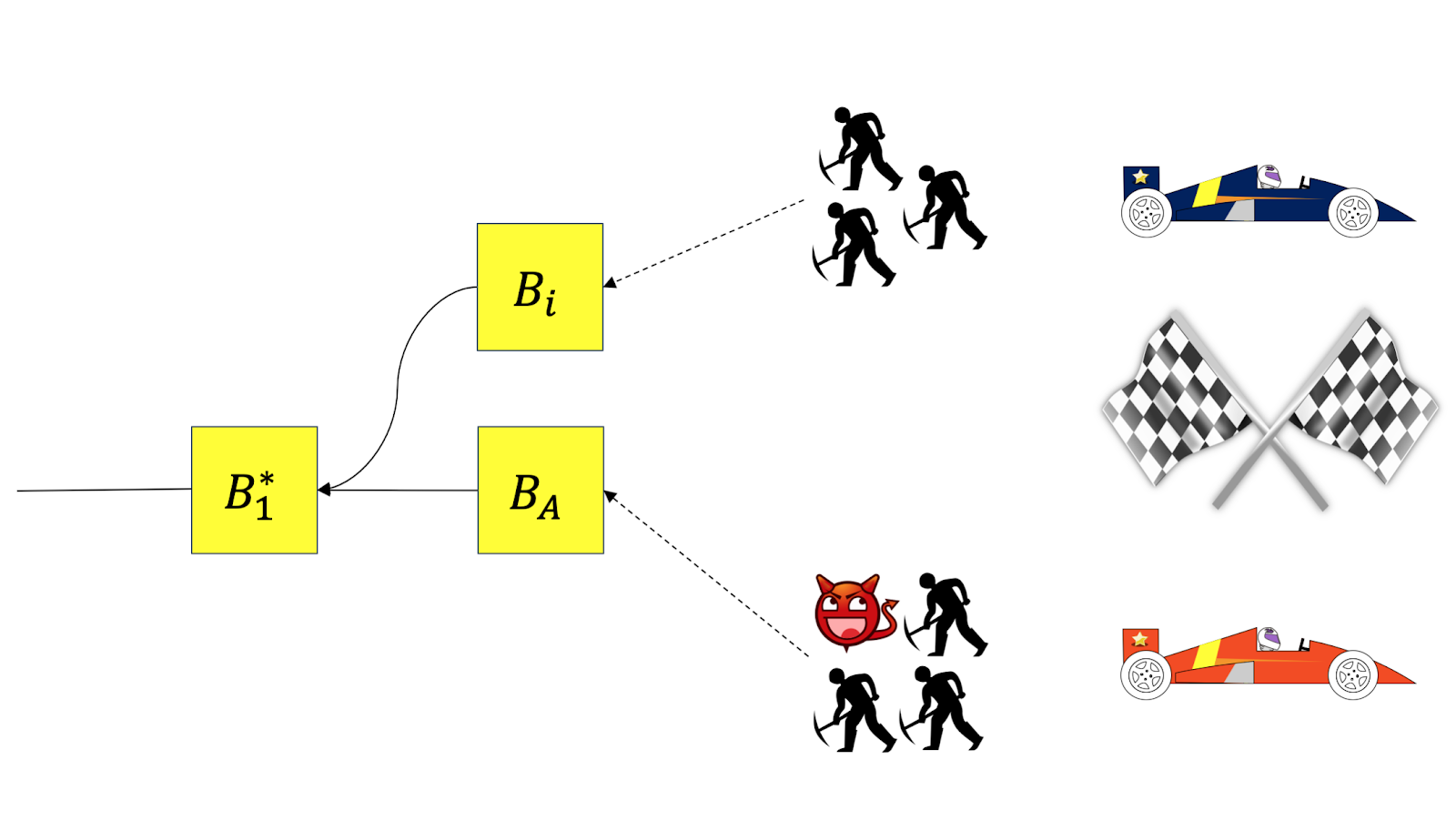

If a rational miner follows option 1 and extends the main chain, finding and broadcasting a new block, the attacking miner uses his relatively high connectivity (as in selfish mining) and propagates the full block corresponding to the header BA. This causes a race between two groups of miners, those that hear of the attacker’s block data first and those that hear of the rational miner’s block first.

With some probability, the rational miner loses the race and the block Bi is never included in the main chain. This reduces the expected reward of mining on the last full block, compared to the “no attack” case.

If the rational miner follows option 2 and successfully extends the attacker’s header BA, the attacker responds by never publishing the full block BA. This causes the block of the rational miner never to be included in the main chain, leading to a zero expected reward from that block.

Therefore if original profitability in the “no attack” setting isn’t too high, in both cases, the attacker can ensure that the honest miner ends up losing money. So the BDoS attacker’s threat means that the honest miner is better off giving up and just not mining, i.e., going with option 3. As it was put famously in the movie War Games, “The only winning move is not to play.”

Conditions for BDoS Success

We now explain under what conditions the attacker succeeds. Specifically, we consider, for specific rational miner i, the conditions under which it is more profitable for i to stop mining than to keep mining, regardless of other players’ actions. The answer depends on three elements. First, the attack will succeed if the hash rate of the attacker is sufficiently large. Second, it will succeed if the hash rate of miner i is small enough. Finally, it will succeed if miner i wasn’t making much profit in the first place.

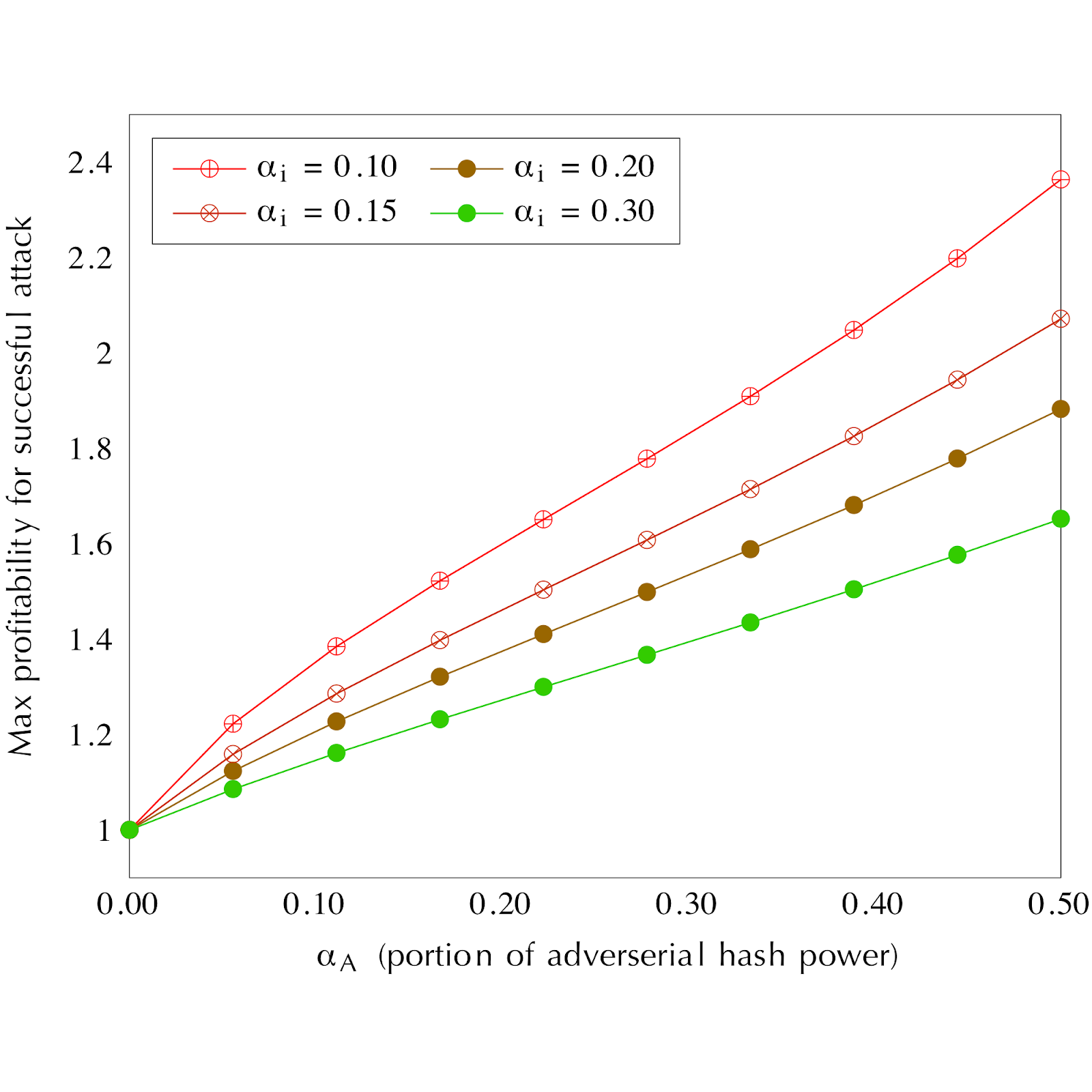

Miner i’s profitability factor is her return on every dollar of investment in mining if there is no attack taking place. We show in the figure below the maximal profitability that admits of a successful attack for different attacker sizes (X-axis) and miner sizes (different curves).

For our analysis, we use a property called profitability factor which represents the return per dollar investment. It depends on mining equipment and electricity costs, as well as the price of the currency being mined.

As a concrete example, if the largest miner’s fraction of the total mining power is 20%, an adversary with a 20% hash rate can incentivize all miners to stop if their profitability factor is below 1.37.

Currently, for Bitcoin, the profitability for Bitmain Antminer S17 Pro with electricity prices of $0.05/kWh is close to 2, while for Antminer S9 the profitability is close to 1. In case of a major price drop a difficulty increase, an attacker would be able to incentivize existing miners to stop mining, leading to a complete shutdown of Bitcoin. Additionally, the block reward is expected to halve in 2020, reducing profitability proportionally.

Two-Coin Model

Note that our model is generous, in the sense of underestimating the opportunity for an attacker. Thus far, we’ve assumed that a miner can either mine or stop mining with profit to zero. However, cryptocurrency miners can often shift their mining efforts to a second currency, even temporarily. If the initial profitability (before the attack) of the two coins is similar, switching to the other coin is almost always profitable if there is an attack. This means that the threat of the attack in this setting, which we call the two-coin model, is even higher than our analysis above suggests. In fact, the two-coin model is a realistic scenario. For example, there is evidence that miners regularly switch between Bitcoin and Bitcoin Cash, depending on the profitability ratio.

Mitigations and Responsible Disclosure

Rather than renting some mining equipment, shorting Bitcoin, and retiring to a country without an extradition treaty, we followed ethical security research best practices and went through a period of responsible disclosure. We alerted the developers of affected prominent cryptocurrencies of the attack and discussed mitigations.

We suggest a small change to the consensus rules such that miners give lower priority to blocks whose header was known more than some threshold time (e.g., 1 min) before the block’s body. This would increase the chance that an attacker would lose a block-propagation race and therefore would reduce the effectiveness of a BDoS attack. Unfortunately, this countermeasure isn’t definitive. As we explain in our paper, an attacker can use smart contracts or ZK proofs to prove she found a block (instead of publishing block headers). With the use of such techniques, it may not be possible to distinguish between the attacker’s block and a rational miner’s in a race, rendering the mitigation technique ineffective.

Another possible solution for BDoS attacks is the use of the uncle block reward mechanism, as in Ethereum. The uncle block reward mechanism grants a reward to a miner that has mined a block that did not end up in the main chain but is connected to it directly. Given the use of uncle block rewards, a rational miner would have a much lower incentive to stop mining in a BDoS attack, because even if she loses the race, she would get a reward (as much as ⅞ of the full block reward in Ethereum). There is a tradeoff, though, as uncle blocks reduce security against selfish mining attacks. Additionally, an alternative BDoS-like attack might use longer than one-header chains to make race loss critical again.

Conclusion

BDoS is a threat to Nakamoto-consensus blockchains, as it allows denial-of-service with a much smaller hash rate than previous attacks. We have shown how an attacker can skew incentives and lead profit-seeking miners to cease mining activity. Our proposed mitigation is easy to apply (not requiring a network fork), but only affects a specific flavor of BDoS attack. Without stronger mitigations, the liveness of Nakamoto blockchains relies on miners’ willingness to follow the protocol despite revenue loss — -that is, on altruism.

The full details are in our technical report.

We thank Sarah Allen, IC3 Community Manager, for her help in writing this blog post.

Miner image by Ramon Venson [CC BY-SA 3.0]